Our History

From the humble beginnings of a lone California grizzly bear to state-of-the-art animal care and wellness, our rich history explains the evolution of our mission to care, connect, and conserve.

1950s: The Zoological Society

Over the 40 years since its founding in 1954, the San Francisco Zoological Society became a powerful fundraising source for the Zoo, just as Fleishhacker had hoped when he envisioned “…a Zoological Society similar to those established in other large cities. The Zoological Society will aid the Park Commission in the acquisition of rare animals and in the operation of the Zoo.” True to its charter, the Society immediately exerted its influence on the Zoo, developing a master plan in 1956 and obtaining more than 1,300 annual members in its first 10 years.

In 1958, the Society took over the operation of Zoo concessions and was responsible for the development of several exhibits, including the African Scene in 1967, the temporary Panda exhibit in 1984, and Koala Crossing and the Primate Discovery Center in 1985. It also funded important projects like the renovation of the Children’s Zoo in 1964, purchasing medical equipment for the new Zoo Hospital in 1975, and the establishment of the Avian Conservation Center in 1978.

From 1958 to 1968, philanthropist Carroll Soo-Hoo donated 40 animals, including western lowland gorillas, orangutans, cheetahs, Siberian tigers, jaguars, zebras, hippopotamuses, spotted hyena, and wild dogs. These donations contributed greatly to the Zoo’s collection. Carroll bought the animals with an understanding that he could visit with them and he continued to come to the Zoo until his death in 1998.

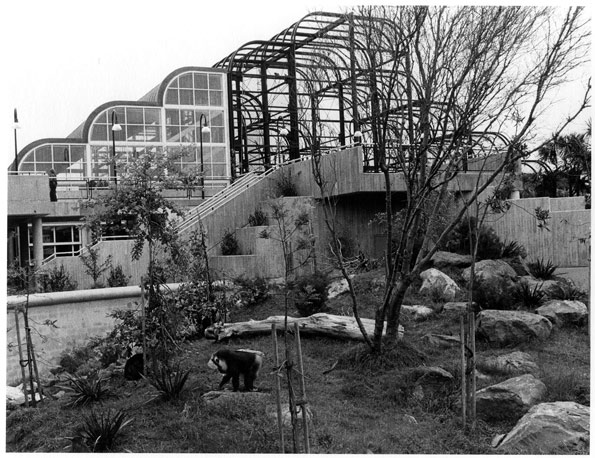

Although the Zoo has benefited from the many improvements in recent years, the original WPA structures had remained virtually untouched since the 1930’s. Then, in 1977, a $2.5 million federal grant enabled the construction of Gorilla World, Wolf Woods, Koala Crossing, the Primate Discovery Center, and Musk Ox Meadow. These exhibits replaced small, sterile enclosures with open, naturalistic habitats that reflect the Zoo’s expanded purposes: conservation, education, recreation, and research. The structures also conformed to Hobart’s prescient vision of naturalistic habitats, where, from a normal distance, “it would appear that the animals were not confined at all.”

The benefits of naturalistic exhibits to the animals were obvious. Bwana and Missy, the Zoo’s first two gorillas, who had come to the Zoo in 1959, spent the first week in their new exhibit learning to pluck grass and climb real trees.

About the Zoo